The design of Radiccio

Thursday, October 30, 2025

Design is about making choices. I wanted Radiccio to feel at home on the Mac. I also wanted it to be a great music player, and to change some things that I found unintuitive or unsatisfying about other music players.

Ideally, usable software should be self-explanatory. If I have to explain why I did something, that is in some way a failure. But I am also curious about the thinking that went into the software that I use every day, and I enjoy reading about it. So for those who may be curious like I am, I thought I would take a moment to write about some of the reasons for the choices I made when designing Radiccio.

I will be the first to admit that I am not the best at visual design. But, as you may have heard, design is more than just that. When I say design, I am focusing on usability, interaction, and experience as much as I am on appearance.

The filesystem

I think the filesystem is underrated. I know that not everyone is comfortable with it these days. But as I said, we have to make choices, and this is one of the earliest ones I made: Radiccio is for people who love the filesystem, who appreciate its power and flexibility, and who are comfortable managing their own files. That is probably going to mean that Radiccio is not for everyone. But it was necessary in order to reach my goals for this app.

In order to use an On My Mac source, you need to supply a folder with audio files already in it. Right away, this is a hurdle that not everyone will be able to get past. But for those that do, I think (and hope) they will understand what I’m going for.

Other players seem like they want to take control of your files; to abstract away the details of the filesystem, so that you don’t have to think about it. Radiccio takes the opposite approach: It leans into the filesystem, expecting you to manage your files the way you want, while adding a layer on top that provides music-specific tools. As I mention frequently on this web site, Radiccio does not modify your files; that is a policy I intend to continue. In this way, Radiccio works alongside Finder, as a complementary tool, rather than a replacement for it.

The right sidebar, album art, and now playing info

The first thing most people notice about the UI is the large space set aside on the right side of the screen for album art, now playing info, and playback controls.

The biggest reason for this is that I wanted to see album art more clearly. For me, the album art is a significant part of the experience of enjoying music. I’ve never understood why most modern Mac music players relegate it to such a tiny, often literally thumbnail-sized area. Even when comparing the iPhone versions of those same apps, there is usually a way to see a large, nearly full-screen version of the artwork and now playing info; while on the Mac, the device with the biggest screens available, this same content is often squished into a narrow horizontal bar. This doesn’t make sense to me.

Some users don’t care about album art, and may consider my design to be a waste of space. But I think there are already plenty of existing options for music player apps whose design condenses this content into the smallest possible space. There are not as many apps that give it enough room to be appreciated. I decided that mine would be one of the latter.

And as a bonus, I made it so that you can always click on the art to see an even larger version in Quick Look. It’s a mystery to me why every app doesn’t do this.

(Trying to avoid) truncation

Music is art, and art is messy. That extends to metadata like the song title, album name, and even artist name, which don’t necessarily conform to anyone’s expectations. Perhaps this may seem like a trivial complaint, but it bothers me when any of these get clipped off, and I can’t see the entire text in the UI. Even if I know what it says (which I may not), it feels like we could try to be a little more respectful of the art.

I also feel that the auto-scrolling, marquee-like effect that you see in some apps has usability problems. What reason is there for making me wait for an animation to complete just so I can read a few words of text? Moreover, what is it about a music player that justifies such unique treatment of a line of text, the likes of which you would find nowhere else in any software?

In Radiccio, I have tried to make sure that each of these metadata elements are visible in their entirety in at least one place somewhere in the UI, even if it is not practicable to display them in full everywhere they appear. In the contexts where they would be the most relevant, I attempt to wrap them onto multiple lines, without any defined limit.

I need to give SwiftUI some credit, for making this much easier than it likely would have been in AppKit. However, the flip side of this is that SwiftUI has its own internal logic about how to manage layout, which is sometimes hard for me to understand or predict. As a result, it’s not really feasible to guarantee that the text will never be truncated, depending on factors like the window size. But in my testing so far, I have been pretty happy with the result; I think it strikes a reasonable balance.

I mention SwiftUI, even though that is an “implementation detail”, because experience has led me to believe that design is inseparable from implementation. The platform and technology you are building on influences the possibilities of what you can make; if you ignore that, the cost is borne by what you are building. In places where design and engineering are specialized into separate teams and individuals, collaboration is key, as always.

Playback controls

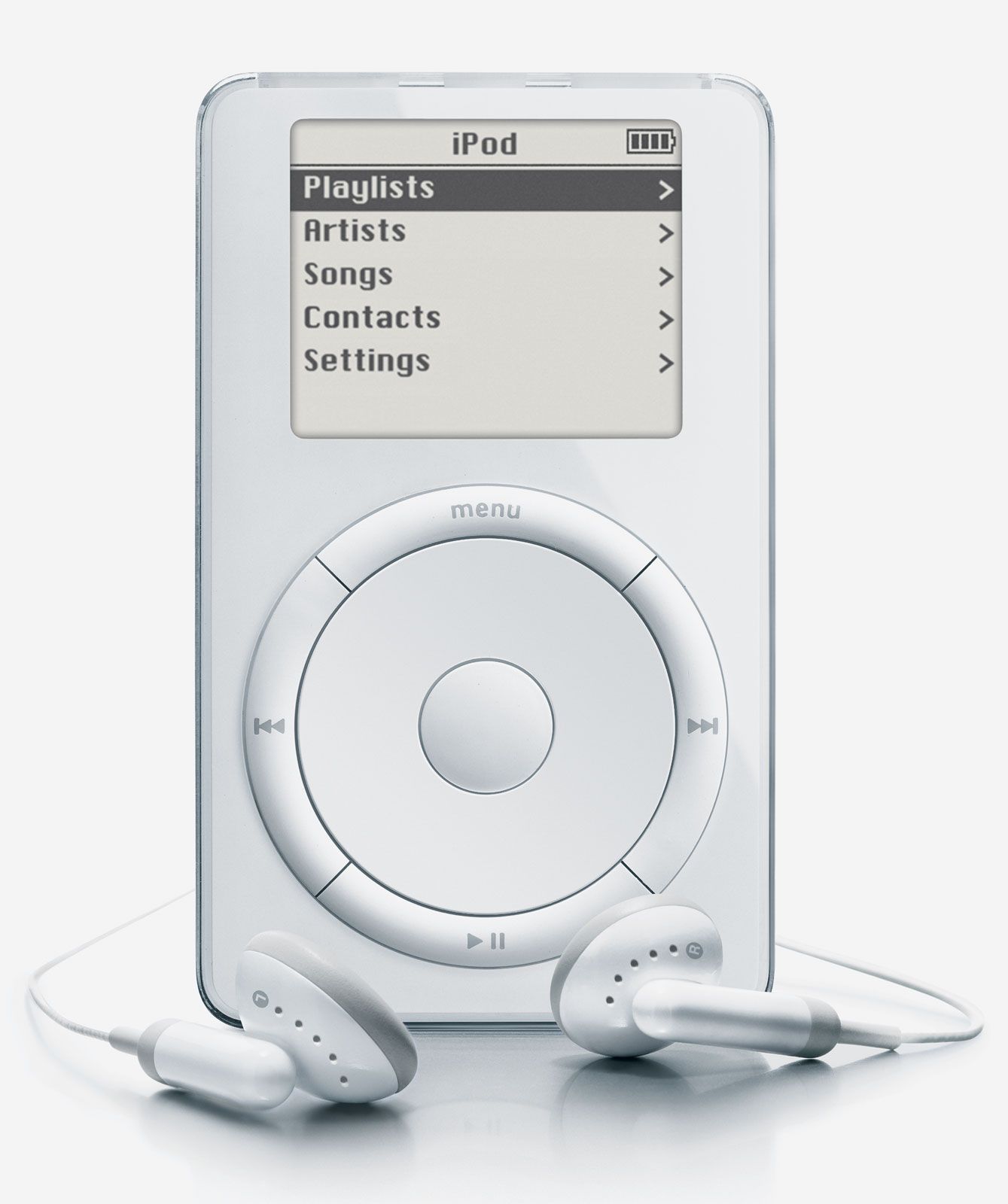

Most recent music player apps have three playback buttons: previous, play/pause, next. This modern convention seems to have been established by iTunes, along with the original iPod, which both shared the same three-button playback controls.

Prior to iTunes, music player apps had varying assortments of playback buttons. Sometimes there was a stop button, and sometimes play and pause were divided into two separate buttons. Most of these designs were influenced by contemporary hardware products, namely, CD players.

In software, unlike hardware, the playback buttons serve a dual purpose; besides the obvious (controlling playback), they can also communicate the current state of playback.

For Radiccio, I brought back the extended set of five playback buttons that used to be more common. My main reason for doing this is that I find it better at communicating state.

For example, consider iTunes’s play/pause toggle: How do you know what the current state is? If you see the pause button, that means it’s playing; if you see the play button, that means it’s not playing. This feels indirect and a little counter-intuitive to me. Hardware devices like the iPod (which was developed concurrently with iTunes) are highly motivated to minimize the number of buttons, in order to keep manufacturing costs down. But software, especially running on a large-screen desktop OS, has no such limitation.

I feel that I can more easily see playback state at a glance when play and pause are separate buttons. I also like being able to easily stop playback, which is a different operation than pause; although not strictly necessary in most cases, the stop button provides a comfortable affordance.

This was a choice I made because I believe the functionality is better this way, and not out of deference for any tradition. That said, I understand that some people may feel more comfortable with the smaller set of buttons that they are used to seeing in other players. So I made a setting that allows you to switch to the other way:

Besides the overall number of buttons, there is another subtle difference in how Radiccio’s controls work; specifically, the behavior of the previous button.

In most players, this button serves two different functions: You can click it once to go to the beginning of the current track, or click it twice to go to the previous track. (That is how most people think of it, but actually, the behavior is determined not by how many times you click, but rather by the current time position of playback. The threshold is not standardized and varies from player to player.)

As best as I can tell, there is no real reason for it to behave this way, other than for the sake of tradition; originally, it was most likely invented due to the need to minimize manufacturing cost for hardware devices, as already discussed.

I think this is unintuitive, and I think tradition by itself is not a complete justification. So, I have discarded this overloaded button behavior. The previous button in Radiccio always goes to the previous track; it never does anything else. I have introduced a separate, smaller button below it, which lets you go back to the start of the current track.

Our screens are big, and our software is unburdened by hardware constraints. Bring on the buttons, I say.

Repeat & shuffle

As mentioned previously, controls in music player apps to this day continue to be influenced by CD players. Those hardware designs needed to minimize the number of buttons, and had non-pixel-based LCD screens which could only show a specific set of symbols that had been permanently set into the display at manufacturing time.

In most apps, the continuation of this tradition results in the repeat control as a three-way toggle button. When you click it, it cycles through several visually noisy symbols. In a vacuum, this does not seem like particularly intuitive software design: What do the symbols mean? When I click the button, which state will it transition to? How many states are there? How many times do I need to click to get what I want? Would this make sense to a user who has never seen a CD player?

I think this is yet another example of something that only persists for the sake of tradition, and for no other apparent reason. We can do better. So why not try? Here is my attempt.

In some apps, shuffle yet again remains mired in past limitations: It’s a simple on/off modal toggle that causes the player to jump around the queue at random, instead of proceeding through the items in order. This might have seemed perfectly reasonable for a CD player, which did not have a user-visible playback queue; there was usually no UI to indicate which song would play next, let alone all of the songs available. In contrast, for a player like Radiccio that makes the queue highly visible (more on that in a moment), this behavior would seem strange.

In Radiccio, shuffle is not a mode; it is an operation. The queue always proceeds to the next item that you can see in the list. Shuffle, instead of changing the behavior of the queue, rearranges the future items in the queue. (But not the past items, because you’ve already listened to them.) And of course, you can undo the shuffle – even after listening to some or all of the songs – which puts the items back in their original order.

In fact, even if you initially started playing an album or playlist in shuffled order, you can still “undo” it to reorder the queue the way it would have been if you had played it normally. Note, however, that if you shuffle and then make further changes to the queue, such as adding, deleting, or manually reordering items, it becomes non-undoable from that point; such operations break the connection between the queue and the original album or playlist that it came from, so there is no logical operation that can reverse the shuffle at that point. Of course, you can always replace the contents of the queue by playing something else.

The queue & playlists

I interact with the playback queue quite a lot. So that is why it is frustrating to me when apps treat the queue as an afterthought, or as a modal or temporary state. I always want to see it. So, in Radiccio, it is given a prominent and permanent place in the UI.

Maybe it is just the way my brain works, but I am constantly making adjustments to the queue on-the-fly. I listen to full albums frequently, but sometimes I want to listen to a really good song a second time…

…or never again.

Sometimes, halfway through an album, I decide I’m not really vibing with it right now, and want to listen to something else. But I want to let the current song finish playing first, so there is no interruption in playback.

I am basically always playing a DJ set for a one-person audience of me. And why shouldn’t it be this easy to do it?

The queue itself, however, looks like nothing particularly special. It is just a basic native list view (technically, a table view). You’ll see the song title, artist and album, and duration. In this case, the utilitarian design is intentional. The queue is a tool; it is not the art itself. It is always there, but it is meant to fade into the background.

The currently-highlighted item is playing. To change which item is playing, simply click on any item; it starts playing immediately.

I dithered on whether or not to include the album art in the queue entries. The way that I use it, I’m usually listening to most or all of an album at once, so in that case, it would just be the same album art repeated many times – visually cluttered and boring. But I know that a lot of people primarily listen to curated playlists, and in that case each song may have different artwork, which would make it more visually interesting. In the end, I decided this would be reasonable case for a settings toggle, although it defaults to “off”.

In order to add, remove, or rearrange items, you have to click the Edit button first. The queue then transitions into edit mode. In this mode, clicking a song doesn’t affect playback, but you can drag-and-drop to rearrange.

This is a decidedly iOS-like UI paradigm, and it would be somewhat fair to paint this as a decision from someone who has more experience on mobile than on Mac. (Guilty.) However, I did have a reason for it: I wanted to avoid accidental drag-and-drop operations when I’m just trying to click, which frequently happens to me in other Mac apps. I also wanted to avoid the reverse – an accidental click during an attempted drag. Sometimes my fingers are clumsy, and the difference between a click and a small drag can be subtle. That kind of mistake, though seemingly trivial, could take me right out of the zone by affecting music playback in a way I didn’t intend, and that’s enough to make me grumpy for a while. With this modal design, you are required to express your intent, so there is no ambiguity about what is going to happen, and no risk of accidentally doing the thing you didn’t intend. I think this design reasonably accomplishes these goals that I had for it.

(There is also a shortcut for quickly removing items by right-clicking to get a context menu. In that case, you don’t need to go into edit mode.)

My intention for the queue is for it to be a playground for creating a transitory music experience that works for you in the moment you find yourself in. But if you happen upon a good moment, wouldn’t it be nice to be able to save it for later? That’s why there is the Save As… button alongside the other queue controls. This creates a playlist in the native format for your current source (in the case of On My Mac source, that’s M3U). This is something I always wished I could do in other music players.

I’m aware that the playlist creation experience in Radiccio feels incomplete, as it is currently. There is more that I still want to do with it.

Don’t forget the Dock

It may seem like a small thing, and many people probably don’t even use it. But I definitely notice when Mac apps don’t have a Dock menu, and I miss it when it’s not there. Especially for a music player app, the Dock menu allows users to control playback without switching to the app, which can be very useful when playing music while doing other things on your Mac.

To see the Dock menu: Click-and-hold on the app icon in the dock; or, click it while holding the “control” key; or, simply right-click it.

In addition to the usual playback controls, Radiccio also lets you change the in-app volume control, or skip to a specific song in the queue (up to 10 songs either back or forward – not too many, to avoid the menu becoming unwieldy). These are two features I haven’t seen in any other apps.

(Fun fact: There is no SwiftUI API to make a Dock menu. Just one of the quite-a-few things I had to make in AppKit.)

The little things

Making an app is a constant stream of small but important decisions. I honestly can’t remember them all, nor would that make for very good reading. But here is a grab bag of some of the more notable ones.

-

The reload button. These are rarely seen in apps lately. I don’t know why. I’ve always felt that pull-to-reload is an abomination, especially on the Mac. Some developers may think “the app will just magically be up-to-date, so there will never be a need to reload” - I’m sorry, but no app has ever successfully achieved this, and you are just creating hundreds of edge cases that will never be fixed. Sometimes, users need to reload. Give them a button. Simple is best. (Of course, ⌘R works, too.)

-

The spinner. The state of the art is the “skeleton screen” which is essentially a bunch of boxes, animated and shimmering, that are supposed to look like content that hasn’t quite loaded in yet. It’s all fake, but I think some research indicated that users think the app feels faster compared to a plain spinner. I wonder how much of this might have been due the research being conducted at a time when it was brand new, which it no longer is. In any case, I think it’s far too noisy. UI needs to indicate progress and spinners are a clear way to do that. Simple is best.

-

The sliding transition animations. When you navigate to a new screen in the middle pane, it smoothly slides in and out. (It’s supposed to, anyway. It may not be as smooth if the app gets bogged down.) This looks like an effect you’re used to seeing on iOS, and you might assume it’s the same one. In fact, I couldn’t find any built-in way to make this happen reliably, so it’s a custom navigation stack that I spent many weeks working on. I rewrote it from scratch multiples times to try to remove all the glitches from the animations. It was a nightmare. I’m happy with how it turned out, though. Worth it. Many people won’t even consciously notice it’s there, but I believe it makes the app feel more polished even so.

-

The volume level number. I’m the kind of person who remembers specifically which numeric volume levels I most frequently use, and I want to be able to make precise adjustments and see exactly what level it is set to. An unlabelled slider is unsatisfying to me, because I never quite know what it is set to, and I have to spend a lot more time making small adjustments until I get it exactly right. So, I made sure that Radiccio shows you a numeric representation of the current volume level, next to the slider. I could have implemented any arbitrary range of numbers, but I picked 0 to 100, in increments of 5. I don’t think I need to explain why a smaller increment would have been torturous; if you know, you know.

-

The Source menu. If you have a smaller laptop screen, don’t forget that you can click a button in the toolbar to collapse the left sidebar. That gives you more space for the rest of the app. Then you can change sources from the Source menu. You can perform all other functions you might need from the menubar, without needing to use the left sidebar at all. I made use of this on my 13” MacBook Air. You might also want to do this if you will only ever have one source.

-

The app name and the app icon. Yes, they do mean something.

Avoidances

For this article, I really wanted to try to avoid sounding too negative about other apps, and the state of the software industry in general – I feel that I may not have quite succeeded at that. In any case, I have tried to consolidate most of my negative items into this section, and I’ll try not to spend too many words on them.

These are things that I wanted Radiccio to not do. And it is certainly neither complete nor exhaustive, but it’s probably more than enough for now.

-

No interruptions. No tutorials. No pop-ups. No “hey you’d better try this new feature, my bonus is depending on it”. The app should try very hard to avoid ever unexpectedly placing any UI in between the user and a goal that they were trying to reach.

-

No distractions. I believe unsolicited content makes the experience worse, and is usually not to the benefit of the user. The app should never show you content unless you specifically asked for it. There should always be a way to hide, remove, or navigate away from unwanted content. Many apps try to coax you into looking at endless feeds of “stuff”, and maybe you want to see that stuff sometimes; it should be available when you want it, but it should not be shoved in your face at every opportunity.

-

No railroading. The user uses the software, not the other way around. The app should wait patiently for the user to decide what to do. Provide explanations as appropriate, but don’t try to tell the user what to do. The app should convey a sense of peace and calm and provide a welcoming environment that the user can play with and customize as they see fit. The app should not nag, pester, or create false urgency in attempt to serve the app developer’s business interests.

-

No upsells. Whether you are using the free or paid version of the app, the UI looks the same. So, if you click on something that requires you to upgrade, you’ll be notified of that. But I’m not going to start throwing annoying ads into the UI to try to convince you to upgrade. (The distinction: the former is a paywall; the latter is an upsell.) I want you to be able to stay on the free version for as long as you’d like, and I want you to have a great experience doing that, even if that means you never upgrade. I want the app to treat everyone the way I would want to be treated. (I hope people understand that if nobody upgrades, it will negatively affect my ability to keep working on the app. But if they don’t understand that, I don’t believe I would convince them by annoying them.)

-

No disappearing UI. Don’t make the user play hide-and-seek with the UI. Primary UI (i.e., the most frequently used controls) should be visible and actionable at all times. Secondary UI should be reachable through something that is visible at all times (e.g., a submenu connected to a button). Don’t fade out, collapse, or minimize the UI after a period of inactivity, or based on scrolling or hover states; this adds significant friction to these interactions. Also, the UI should always have sufficient contrast so that people can comfortably read what it says.

-

No hover states. It drives me bonkers when I’m just moving my mouse around, and a dozen things start lighting up for no reason. Stop it. This upsets my need for peace and calm in my environment. (…So yes, I’ve actually already broken this rule in a few places. But I try to show some restraint. Also, tooltips are a fair exception, but only when strictly necessary for clarification.)

-

Don’t require right-click, or gestures. Users make decisions about how to proceed based on what they can see. Do not expect the user to memorize the app – they won’t! UI should be visible on the screen, and users should be able to interact with it via a single click (or tap). Right-click and gestures can be useful as shortcuts, but they should never be required. All features and functionality should be discoverable, and you can’t get any less discoverable than being completely invisible. The reason why click (and tap) are primary is because they are simple and easy; forcing more complex modes of interaction adds unnecessary friction.

-

Don’t be afraid of error messages. Look, no one likes errors. But they are a fact of life. If an error happens, I’m going to tell you what I know. I might use arcane technical language. It might not make sense. But, two things: You can copy and paste it into a search engine. Or, even better, you can copy and paste it into an email to me, so that I can investigate and hopefully fix it. I think it is really misguided when app makers replace specific, contextual information with generic pacifiers like “We’re sorry!” or “Something went wrong.” or “Oops!” That makes the software less useful, by closing off potential paths forward.

I have used the words “no” and “don’t” quite a few times here. Please understand that this does not literally mean that Radiccio will never do any of these things. These are my goals, and I intend to do my best. Sometimes, I will encounter a problem, and one of these avoidances might be the only way I can find to solve it, for the time being. I promise you that I will feel this failure more than you know. And then I will come back the next day and try to do better.

And finally, back down to earth

Software is only useful to the extent that people use it. This is almost a tautology, but it is nonetheless important enough to remind ourselves. Software design is not merely an abstract exercise; if we are not designing something that humans will actively choose in order to accomplish their goals, then there was no point to any of it. It is all too easy have fun and make something that seems perfect for ourselves, while losing sight of the larger purpose.

Currently, I work for a one-person company. I have tried to draw upon my years of experience in the industry, my lifelong study of software, and my interactions with other people, to create something that I hope others will enjoy as much as I do. But hopes are not reality, and the reality is that it’s really hard to get a good sense of what will (or won’t) resonate with people, especially when working solo. So, to the extent that I have missed some important things, which I’m sure I have, please know that it was not for lack of trying.

Got any feedback? I’m listening.

Thank you, as always, for your interest in Radiccio.

– dmd